Imani

“I am going to see my mother this weekend,” I say. I do not know why I say it, but it seems like the only thing I can say to break the silence hanging above our heads, consuming our comfort, little by little. It is the only thing that seems sayable to a person who I have no idea why I accepted to even meet.

We are seated at a corner of one of the city’s rooftop bars, me sipping my cold freshly-squeezed passion juice, biting the mouth of the plastic straw while at it. I have forgotten the name of the drink she is galloping, even though this is her third glass, or bottle, or whatever thing they use to measure these things.

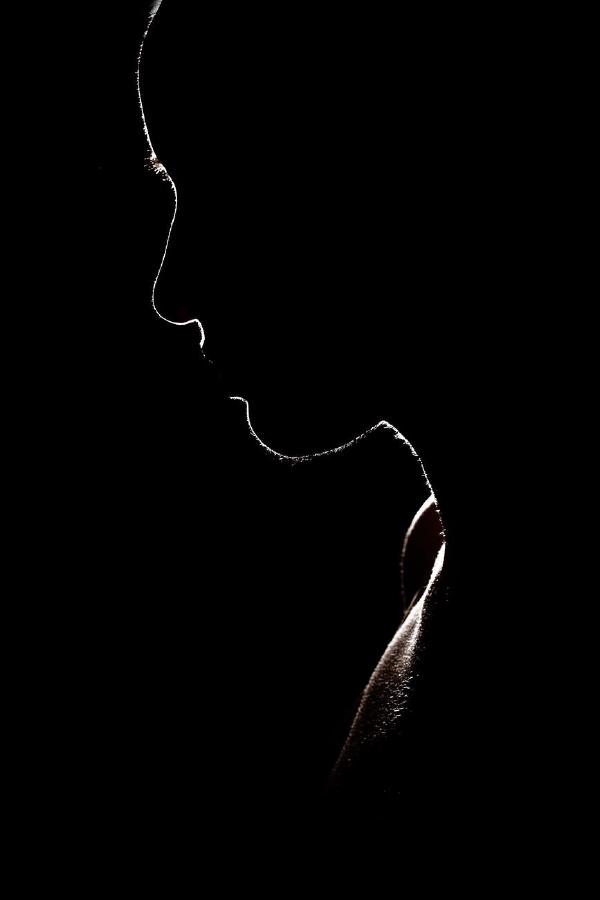

It is my first time in a bar since I was born; a typical bar with old men gazing at little girls' asses, before whispering obscenities among themselves. It is her first time in a bar since the dusk to dawn curfew was lifted. Her face is calm against the evening breeze, against the soft noise of heavy Nairobi traffic below us. Unlike her face, her lips and mouth are noisy; sipping the drink as if the world is ending in five seconds.

There is a drying wound on both of her arms, and when she catches me staring for the third time, she offers an explanation.

“I could have died that day. I should have died that day,” she says, the lashes on her eyes flipping quickly, her otherwise small eyes gazing into the space above my head.

What happened? I want to ask, but my spirit has been in such a bad place recently, rendering me unable to take in other people’s problems. So I feign disinterest, picking the spaces beneath my long nails, wondering why no one is even trying to call me today.

“Aren’t you going to ask what happened?” She asks, lowering her eyes so that they meet mine, and I detect a flash of anger, and sadness, and faint hope in them. “What happened to you?”

I shuffle in my seat, my voice caught up in my throat. I take a slight bite on my straw, taking my focus away from the soft pain in her otherwise calm voice.

“What happened to you? You used to care.”

She goes on and on, but I successfully block the rest from my head. I want to tell her what happened, to me, since four years ago when we last saw each other. That life happened, dragging me out of my illusion that I could save everyone, even without them asking. That it, life, dealt me the hardest of blows, not once, not twice, until I accepted that I am not built that way; picking myself from the trenches, alone, nursing myself back to health, and still making time to take on other people’s burdens.

I want to tell her that these four years have been formative in my becoming; teaching me the basis of simple living; by myself, on my own terms. They have forced me on my knees, asking me the hard questions, and not letting me go until I have made peace with my demons.

I want to tell her that in these four years, I have carried the heaviest burdens, and no one even knew about it. I have cried myself to sleep, waking up to swollen eyes and a crushed spirit, until I couldn’t find the will to live anymore.

I want to tell her why I hold these four years closest to my heart; that I have learnt to walk away from problems that do not belong to me. My heart and soul have made peace with my decision not to take up anyone’s baggage, no matter how small it is. That my body has started shaking off these foreign weights, revealing parts of me that I wasn’t aware were this beautiful.

I want to tell her how my heart has grown light, and fancy, and unattached to things that do not bring me joy. So that when someone asks whether they can vent to me, I do not feel guilty when I say no. l I do not beat myself for walking out every time someone starts talking about their sadness and pain, or life and death.

Sleep does not evade me whenever someone pours their problems to me, without asking, and the only thing I manage to say is, ‘That sounds hard,’ or the proverbial ‘Wah, sa utadu?’ that Kenyans have mastered.

I want to tell her all these, but my voice is still stuck in my throat, rendering me speechless.

“What happened?” I manage to ask when her eyes totally refuse to let me go.

Then it starts. Her voice bouncing off my ears, breaking my heart into pieces. She goes on and on about her initial pleas for the police to let her go being met by their rough, ‘msichana mrembo kama wewe hujui masaa ya curfew imefika?” About her finally giving in, and letting them have their way with her, with a promise for freedom. About her beginning to resist, when their number became more than she anticipated. About her resistance being met by heavy blows first on her head, before she found the strength to block them using her arms, and the voice in her throat letting out a scream.

“You should have seen my mother’s face when I finally made it home,” she says, snapping me out of my reverie.

“How was it?” I ask. “Your mother’s face, I mean.”

This time, I let myself feel everything she says. I try to not lose my mind, even when she speaks of her mother in ways I am still finding hard to imagine. Not even when she says she, the mother, couldn’t let her in because ‘all that had happened was her fault’. Not even when she says she sat with the pain and shame for three months, until something within her body started to fail, and she found out she has HIV.

We sit in silence, each to their own thoughts, until her eyes finally find mine and she asks, “You said you are going to see your mother this weekend. May I come with you, please?”

“Why?” I ask.

“I want to see how a true mother looks like. A mother who laughs with their child. A mother who misses their child, so she calls them every now and then. A mother who has had books written in her honour. A mother whose presence shows in the face of their children. Maybe then, I will understand…”

Her phone lights up, ringing, the name ‘Mother’ plastered across the screen. I watch as anger washes over her face, before she picks up her handbag, pulls back her chair, and starts to leave. On her seat, she leaves a tattered diary with a huge branding on the front: IMANI.

{Our blog, this one, made it to the finalist list of Afrobloggers awards. Kindly vote for it by clicking here. Scroll to the Creative Writing category and vote for Heart and Soul (https://www.mbabaziafrica.com). Thank you.}